DOCTOR CHUCK RADIS

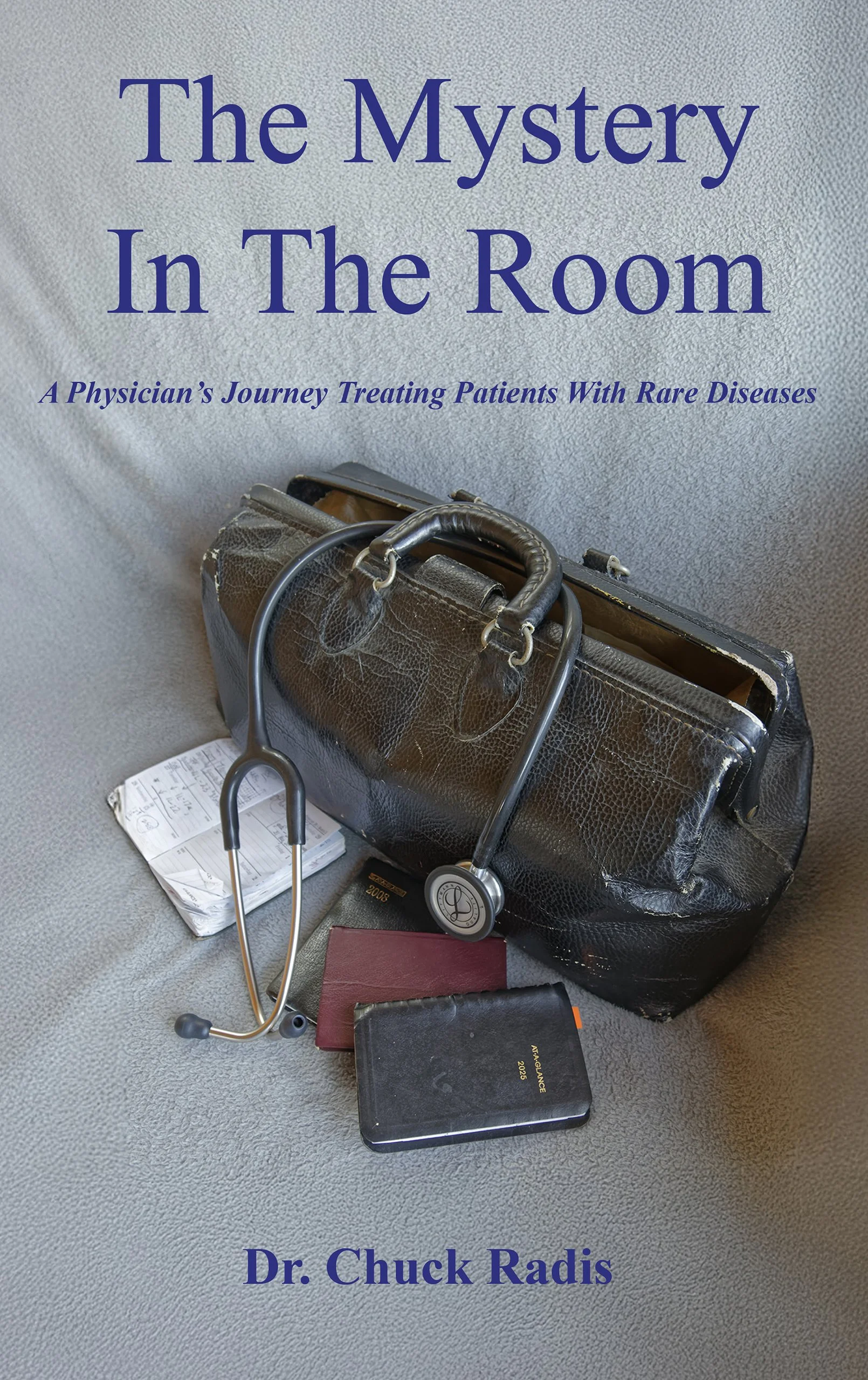

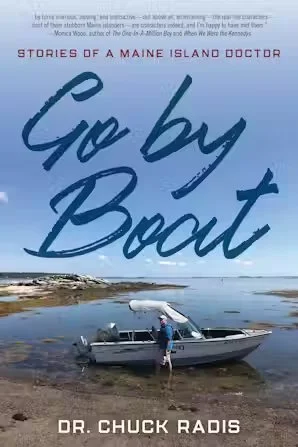

Dr. Chuck Radis is the author of The Mystery in the Room, Go by Boat, Island Medicine, John Jenkins: the Mayor of Maine, and co-authored (with the “Botany Brothers,” Steve and Rick Radis) Wildflowers of Casco Bay.

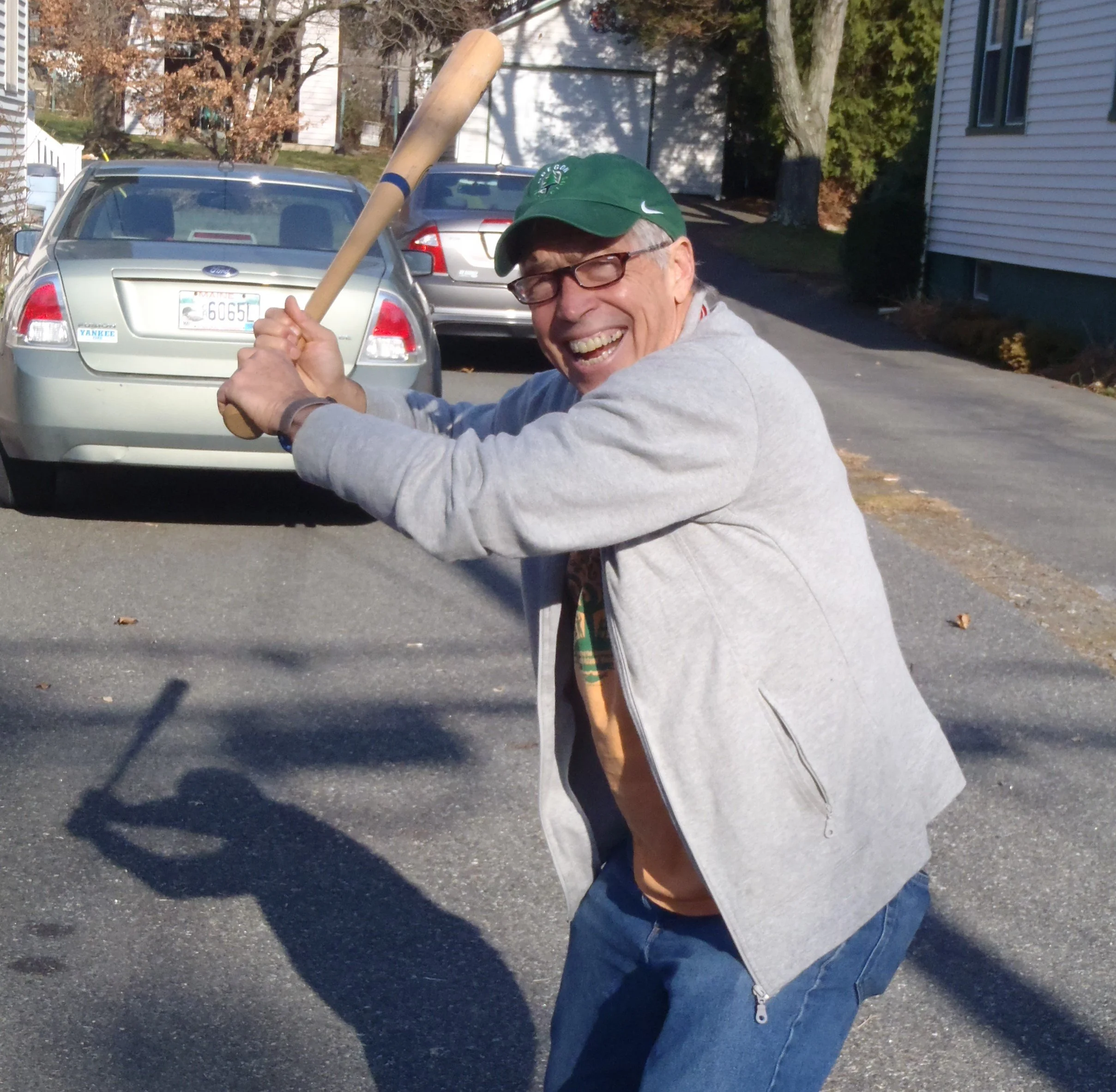

Throughout his years as a primary care physician, and later, as a rheumatologist, Dr. Radis’s writing has appeared both in medical journals and in the popular press on topics such as empathy and kindness in medicine, the narcotic epidemic, and the logic of expanding Medicare for all Americans. As a long-time Peaks Islander, his stories offer readers a glimpse into a world of ferry travel, unusual animal visitations, scallop harvesting and lobstering; a place where island grudges (and unlikely friendships) are maintained for decades.

Every patient has a story to tell. But not every patient has the good fortune to be cared for by a gifted storyteller like Dr. Chuck Radis. He is a true raconteur, relating stories of medical derring-do and near misses in an eminently approachable style."

— Philip Seo, MD, MHS, Associate Professor of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University of Medicine.

Island Medicine “…puts a human face on the personal and physical challenges of practicing medicine. [Radis] joins the ranks of writing physicians such as Abraham Verghese and the late Richard Selzer.”

—Lloyd Sachs, books critic, Chicago Tribune and Kirkus Reviews

John Jenkins: Mayor of Maine captures the exuberance and proud legacy of a champion for Lewiston and Auburn who gave inspiration and hope to countless people throughout the region and the state of Maine.”

—Governor Janet T. Mills.

Go By Boat is “…by turns hilarious, moving, and instructive—but above all, entertaining—-the real-life characters—most of them stubborn Maine islanders—are characters indeed, and I’m happy to have met them.”

—Monica Wood, author of The One-In-A Million Boy and When We Were the Kennedys.

Wild Flowers of Casco Bay is the perfect Birthday or Holiday gift for Maine friends interested in the islands of Casco Bay off the coast of Southern Maine.

Social Justice & Non-Profit Work

Dr. Radis’ projects in South Sudan developed out of his contacts with South Sudanese refugees in Portland, Maine in 2013. His more recent public health work has been in the United Nations Kiryandongo Refugee Settlement in northern Uganda. He is a co-founder of the Maine-African Partnership for Social Justice (MAPSJ), a 501c(3) non-profit, along with his wife, Sandra Radis, and Dr. Daniel Crothers.